Exhibition dates: 15th March – 15th July 2018

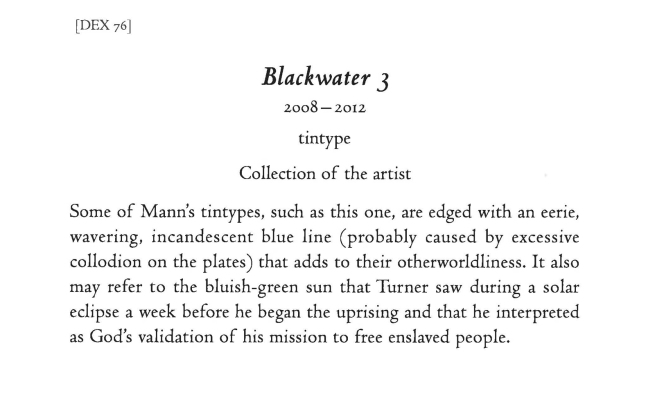

Presented in conjunction with the exhibition Colony: Frontier Wars (15 March – 2 September 2018) which presents a powerful response to colonisation through a range of historical and contemporary works by Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists dating from pre-contact times to present day.

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this posting contains images and names of people who may have since passed away.

![Installation view of the entrance to the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the entrance to the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the entrance to the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation views of the entrance to the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne featuring 19th century Aboriginal shields from the NGV Collection

Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

This is an ambitious double exhibition from the National Gallery of Victoria: historical with a contemporary response. I didn’t have time to take installation photographs of the contemporary exhibition on Level 3 during the media call, concentrating instead on Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861, the historical exhibition on the ground floor of NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne.

A review, along with the installation photographs of the many early photographs present in the exhibition, will be presented in Part 2 of the posting.

Suffice to say that his exhibition should not be missed by any Australian.

Marcus

.

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Victoria for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All installation photographs © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria.

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Eastern Australia 1788-1872

![Colonial Frontier Massacres in Eastern Australia 1788-1872 from The Centre for 21st Century Humanities, The University of Newcastle]()

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Eastern Australia 1788-1872 from The Centre for 21st Century Humanities, The University of Newcastle

![Unknown. 'Broad shield' (early 19th century-mid 19th century)]()

Unknown

Broad shield (early 19th century-mid 19th century)

earth pigments on wood, cane, pipeclay

91.3 x 19.5 x 9.5 cm irreg.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Felton Bequest, 2011

Shields

Aboriginal people have occupied the Australian continent for more than 65,000 years. The arrival and settlement of Europeans, from 1788, affected them profoundly. This proud massing of nineteenth-century shields at the entrance to this exhibition serves as both a reminder of the resilience of Aboriginal people in the face of colonisation, and a representation of the first chapter in Australian art.

The painted and incised designs on the shields are signifiers of the identities and places of these artists whose names, language groups and precise locations were not recorded by European collectors.

There are two kinds of shields traditional to south-east Australia. The first type is narrow and fashioned from a single piece of hardwood, designed to block the forceful blows of clubs, usually in individual combat, and is called a parrying shield. The second is broad and thin with a convex outer face and concave under-surface, and is fashioned from the outer bark or cambium. It is known as a broad or spear shield. This type of shield deflects sharply barbed spears thrown in general fights and also has a ceremonial purpose. These precious cultural objects are of inestimable value to Aboriginal people today. (Text from the NGV website)

![Melchisédec Thévenot (cartographer, French c. 1620-1692) New Holland, revealed 1644: Terra Australis, discovered 1644 (Hollandia Nova detecta 1644: Terre Australe decouverte l'an 1644)]()

Melchisédec Thévenot (cartographer, French c. 1620-1692)

New Holland, revealed 1644: Terra Australis, discovered 1644 (Hollandia Nova detecta 1644: Terre Australe decouverte l’an 1644)

1644

Ink on paper

50.0 x 37.0 cm

Published in De l’imprimerie de Iaqves Langlois, 1663

National Library of Australia, Canberra

Photo: National Library of Australia

Included in Melchisédec Thévenot’s travel account of 1663, this is the first published large-scale map of Australia. It shows how much of the continent’s coastline was known to Europeans 100 years before James Cook’s Pacific voyages, which would substantially complete European cartographic knowledge about both Australia and New Zealand. Thévenot’s map was published when French colonial aspirations were expanding and it divides the continent along the 135-degree meridian, which marked the western limit of Spain’s imperial claim in the South Pacific. Designating the eastern, undescribed expanse in French (‘Terre Australe’), the map signals French interest in the land east of New Holland. (Exhibition text)

European exploration before 1770

The notion that James Cook ‘discovered’ Australia denies the presence of Aboriginal people for 65,000 years and overlooks other European and regional visitors to the Australian coast. The existence of a great southern land, Terra Australis, had long exercised Europeans’ imaginings about the world and began to take a more realistic shape on maps in the early seventeenth century because of maritime exploration. The earliest documented European contact was that of Willem Janszoon and his crew aboard the Dutch ship Duyken, which landed on the west coast of Cape York Peninsula in 1606.

Subsequently, a number of navigators on Dutch and English ships charted the west coast of the continent. Dutch explorer and trader Abel Tasman mapped the west and southern coasts of Van Diemen’s Land in 1642. Two years later, on his second voyage, he reached the north and west coast of Australia, which he named New Holland. The British privateer William Dampier reached the west coast in 1688, and trade between Aboriginal people and the Makassans (from modern-day Indonesia) is documented from around 1720. The Dutch charts of the western coast of Australia were known to the British for more than a century before Cook set sail on his first Pacific voyage. (Text from the NGV website)

![Unknown 'Beardman jug, from the wreck site of Vergulde Draeck' before 1656]()

Unknown

Beardman jug, from the wreck site of Vergulde Draeck

before 1656

Earthenware Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney

Transferred from Australian Netherlands Committee on Old Dutch Shipwrecks, 1991

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Thirty years after the Batavia was wrecked off the Australian west coast, the VOC ship Vergulde Draeck was destroyed on a reef 100 kilometres north of current-day Perth. More than 300 years later, in 1963, the submerged wreck was discovered by fisherman, and a large quantity of gold and silver bullion and German beardman or bellarmine jugs retrieved from within. The latter name is popularly associated with late sixteenth- to early seventeenth-century cardinal Robert Bellarmine, an opponent of Protestantism who was known for his fierce anti-alcohol stance. These potbellied, anthropomorphic jugs were certainly intended to ridicule him; they were regularly used to store wine. (Exhibition text)

![Unknown 'Beardman jug, from the wreck site of Vergulde Draeck' before 1656]()

Unknown

Beardman jug, from the wreck site of Vergulde Draeck

before 1656

Earthenware Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney

Transferred from Australian Netherlands Committee on Old Dutch Shipwrecks, 1991

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Isaac Gilsemans (cartographer) 'Coastal profiles of Van Diemen's Land, 4-5 December 1642']()

Isaac Gilsemans (cartographer)

Coastal profiles of Van Diemen’s Land, 4-5 December 1642

1642

Bound into Extract from the Journal of the Skipper Commander Abel Janssen Tasman kept by himself in discovering the unknown Southland 1642-43, compiled c. 1643-47

Pen and ink

23.5 x 37.6 cm

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Acquired from Martinus Nijhoff, 1926

![Victor Victorszoon (draughtsman) Johannes van Keulen II. 'Amsterdam Island, St Paul Island, Black swans near Rottnest Island' c. 1724-26]()

Victor Victorszoon (draughtsman)

Johannes van Keulen II

Amsterdam Island, St Paul Island, Black swans near Rottnest Island

c. 1724-26

Plate from Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien (The Old and New East Indies) by François Valentijn, vol. 3, part 2, published by Johannes von Braam and Gerard Onder de Linden, Dordrect and Amsterdam, 1724–26

Engraving

30.4 x 18.5 cm (plate), 34.7 x 22.1 cm (sheet)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

J.C. Earl Bequest Fund 2011

![William Ellis. 'View of Adventure Bay, Van Diemen's Land, New Holland' 1777]()

William Ellis (England 1751 – Belgium 1785, Australia 1777)

View of Adventure Bay, Van Diemen’s Land, New Holland

1777

Watercolour and brush and ink

20.0 x 47.3 cm

National Library of Australia, Canberra

William Ellis served as surgeon’s mate on Cook’s Third Voyage and doubled his duties as unofficial natural history draughtsman, producing numerous sketches and watercolours. In these two watercolours he documents the Discovery and the Resolution harboured in the calm waters of Adventure Bay on Bruny Island, and the distinctive geological features of Fluted Cape at the southern end of the bay. (Exhibition text)

![William Bradley. 'Botany Bay. Sirius & Convoy going in: Supply & Agents Division in the Bay. 21 Janry 1788']()

William Bradley (England c. 1757 – France 1833, Australia 1788-91)

Botany Bay. Sirius & Convoy going in: Supply & Agents Division in the Bay. 21 Janry 1788

opposite p. 56 in his A Voyage to New South Wales 1786-92, compiled 1802

Watercolour and pen and ink

19.0 x 24.3 cm (sheet)

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

William Bradley sailed with the First Fleet as first lieutenant on board HMS Sirius and remained in the colony until 1792. Like many officers he kept a journal, illustrating key events. This work shows the First Fleet’s second contingent of ships sailing in to Botany Bay to join the advance party already anchored there. Signed and dated 21 January 1788, this and other Bradley images are significant eyewitness accounts of history in the making. Bradley compiled this journal after 1802, and may have made copies of earlier drawings. (Exhibition text)

Landing and settlement at Sydney Cove 1788

Although Botany Bay had been chosen as the site for the establishment of the new penal colony, within days of arriving in January 1788, Governor Arthur Phillip relocated the First Fleet north to Sydney Cove in Port Jackson. Here the ships could be safely anchored and a freshwater stream provided a crucial water supply around which the first rudimentary settlement of tents, huts and the governor’s residence was established. The early years were extremely difficult and the colony faced starvation as the crops failed due to the lack of skilled farmers, unfamiliar climate and poor soil. But as farming pushed into more arable lands during the 1790s, settlement expanded and new townships were laid out, competing for resources with the Aboriginal inhabitants and dispossessing them of their lands.

No official artists accompanied the First Fleet and the colony’s earliest works of art were drawings made by officers trained in draughtsmanship and convicts with artistic skills. These drawings largely comprised ethnographic records of local people, natural history images of flora and fauna, charts and coastal views of the harbour’s topography. By the early years of the nineteenth century views of Sydney emphasised its growth, as urban development symbolised for the colonists the progress of Empire. (Text from the NGV website)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation views of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with in the bottom image at right, Sketch and description of the settlement at Sydney Cove, Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland 1788; and second right top, View of the entrance into Port Jackson taken from a boat lying under the North Head c. 1790

Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Francis Fowkes (draughtsman) Samuel John Neele (etcher) 'Sketch and description of the settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland' 1788]()

Francis Fowkes (draughtsman)

Samuel John Neele (etcher)

Sketch and description of the settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland

1788

Hand-coloured etching and engraving published by R. Cribb, London, 24 July 1789

19.6 x 31.7 cm (image), 26.8 x 38.7 cm (sheet)

National Library of Australia, Canberra

Dated 16 April 1788, this extremely rare map (there are only three known copies) was drawn by former navy midshipman and convict, Francis Fowkes, some three months after the First Fleet arrived in New South Wales. Published in London in July 1789, it presents a schematised view of the infant settlement with buildings, tents, sawpits, workshops, storehouses, quarries and gardens identified in the key. The eleven ships of the First Fleet are shown at anchor and the Governor’s ‘mansion’ is clearly identified on the eastern side of the cove. (Exhibition text)

![Port Jackson Painter. 'View of the entrance into Port Jackson taken from a boat lying under the North Head' c. 1790]()

Port Jackson Painter

View of the entrance into Port Jackson taken from a boat lying under the North Head

c. 1790

Watercolour

11.7 x 24.2 cm

Rex Nan Kivell Collection: National Library of Australia and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with at left lower, George Tobin’s Native Hut (or Wigwam) of Adventure Bay, Van Diemans [Diemen’s] Land 1792 folio 16 in his Sketches on H.M.S. Providence; including some sketches from later voyages on Thetis and Princess Charlotte album 1791-1831 watercolour. State Library of New South Wales, Sydney Acquired from Truslove and Hanson, in 1915 – in the image below at bottom left.

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with at bottom centre, Sarah Stone’s Shells 1781

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Sarah Stone. 'Shells' 1781]()

Sarah Stone

Shells

1781

Watercolour over black pencil

43.0 x 58.0 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 2016

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with at left, View of the town of Sydney in the colony of New South Wales c. 1799; and second left of the row of four, Juan Ravenet’s Convicts in New Holland (Convictos en la Nueva Olanda) and English in New Holland (Ingleses en la Nueva Olanda) 1789-94 (see below)

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Unknown artist. 'View of the town of Sydney in the colony of New South Wales' c. 1799]()

Unknown artist (England)

Thomas Watling (after)

View of the town of Sydney in the colony of New South Wales

c. 1799

Oil on canvas

65.0 x 133.0 cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Gift of M.J.M. Carter AO through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation in recognition of the abilities of James Bennett to promote public awareness and appreciation of Asian art and culture 2015

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

Transportation to New South Wales

The favourable accounts of New South Wales by James Cook and Joseph Banks were influential in the government’s selection of Botany Bay as the site for a new penal colony. Britain’s loss of the American colonies in 1783 ended convict transportation across the Atlantic and increased the pressure for new solutions to the rising rates of crime and incarceration experienced in late eighteenth-century Britain. The founding of a penal settlement in New South Wales was perceived not only as providing a solution to domestic, social and political problems but also as holding the key to territorial expansion in the South Pacific and the promotion of imperial trade.

The lengthy preparation for the First Fleet raised huge public interest. For most people at that time it was a journey of unimaginable length to a place as remote and unknown as the moon. The eleven ships comprising the First Fleet left Portsmouth in May 1787 with more than 1300 men, women and children on board. Although most were British, there were also African, American and French convicts. After a voyage of eight months the First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay in January 1788. (Text from the NGV website)

![Unknown. 'Transported for sedition' 1793 (installation view)]()

Unknown

Transported for sedition (installation view)

1793

Woodcut on linen

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

This printed linen handkerchief shows five men popularly known as the ‘Scottish martyrs’. In 1794 they were sentenced to transportation to New South Wales for terms of up to fourteen years for the crime of sedition – inciting rebellion against the government of Britain. When published, or printed on paper, images such as this were also considered seditious and censored. Printed handkerchiefs, however, were not subjected to the same sanctions. They had the added advantage of being easily concealed and, when safe to do so, were displayed to show the owner’s political affiliation. (Exhibition text)

![Juan Ravenet. 'Convicts in New Holland (Convictos en la Nueva Olanda)' 1789-94]()

Juan Ravenet (Italy 1766 – Spain c. 1821)

Convicts in New Holland (Convictos en la Nueva Olanda)

1789-94

From an album of drawings made on the Spanish Scientific Expedition to Australia and the Pacific in the ships Descubierta and Atrevida under the command of Alessandro Malaspina, 1789-94

Brush and ink and wash

19.5 x 12.5 cm

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

![Juan Ravenet. 'English in New Holland (Ingleses en la Nueva Olanda)' 1789-94]()

Juan Ravenet (Italy 1766 – Spain c. 1821)

English in New Holland (Ingleses en la Nueva Olanda)

1789-94

From an album of drawings made on the Spanish Scientific Expedition to Australia and the Pacific in the ships Descubierta and Atrevida under the command of Alessandro Malaspina, 1789-94

Brush and ink and wash

19.5 x 12.5 cm

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Extremely few realistic depictions of convicts in Australia are known. These rare portraits, showing garments worn by male and female convicts and by officials, were painted by one of two artists on board the Spanish expedition (1789-94), led by Alessandro Malaspina, that visited Sydney in 1793. A major scientific expedition, like Cook’s and La Pérouse’s, the visit also had political implications, as Sydney formed a strategic British base in the Pacific that could threaten Spanish interests in the Americas and Philippines. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with at left, Half-length portrait of Gna-na-gna-na c. 1790

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Port Jackson Painter. 'Half-length portrait of Gna-na-gna-na' c. 1790]()

Port Jackson Painter

Half-length portrait of Gna-na-gna-na

c. 1790

Gouache

29.4 x 24.0 cm

National Library of Australia, Canberra

Rex Nan Kivell Collection

Indigenous representation

In the early years of settlement there was little contact with the Eora, the Traditional Owners of the area around Sydney Cove, who actively avoided the new arrivals, but as the colony grew, communication, and occasionally friendships, developed. The English had little understanding of the deep relationship between the Eora and their lands, and their careful management of resources, which were soon overstretched by the colonists. Famine and introduced diseases also devastated numerous communities. As the nineteenth century progressed, traditional life along the east coast of Australia was irrevocably changed.

Early images of Aboriginal people reflect the curiosity of the early colonists. Studies of the material culture of Indigenous people, and attempts to record everyday activities ranging from ceremonial gatherings to fishing and hunting, reveal the Europeans’ desire to understand Aboriginal people and culture through ethnographic documentation. Importantly, a number of these portraits include the names of the people depicted – they are not generic representations. The European artists who made these images were fascinated by the appearance of the individuals they encountered, sometimes producing finely detailed drawings and watercolours showing the particulars of hairstyles, ornamentation and scarification. (Text from the NGV website)

![Piron and Copia. 'Natives of Cape Diemen fishing (Pêche des sauvages du Cap de Diemen)' 1800]()

Jean Piron (draughtsman, Belgium 1767/1771 – south-east Asia after 1795)

Jacques Louis Copia (engraver, Germany 1764-99)

Natives of Cape Diemen fishing (Pêche des sauvages du Cap de Diemen)

1800

Plate 4 from the Atlas pour servir à relation du Voyage à la Recherche de La Pérouse (Atlas of the voyage in search of La Pérouse), by J-J. H. de Labillardière, published by Chez Dabo, Paris 1817

Etching and engraving

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Foundation, 2017

Jean Piron was an artist trained in the Neoclassical tradition who accompanied the expedition led by Admiral Joseph-Antoine Raymond Bruni D’Entrecasteaux during 1791-94. His drawings from this expedition are the earliest surviving visual observations of the Aboriginal people of Tasmania by French explorers. Prints, engraved after his death, show Piron’s idealised vision of Tasmanian Aboriginal people living in tranquil harmony with their surroundings. However, apart from the spear-throwing man and the accurately depicted fibre and kelp baskets, there is little to indicate Tasmania in the classicised representation of the landscape and its people. (Exhibition text)

![Samuel John Neele (etcher, England 1758-1825) 'Pimbloy [Pemuluwuy], native of New Holland in a canoe of that country' 1804]()

Unknown artist (draughtsman, active in England early 19th century)

Samuel John Neele (etcher, England 1758-1825)

Pimbloy [Pemuluwuy], native of New Holland in a canoe of that country

1804

Following p. 170 in The Narrative of a Voyage of Discovery in his Majesty’s vessel the Lady Nelson by James Grant, published by Thomas Egerton, London, 1803

Etching

Special Collections, Deakin University, Melbourne

Pemuluwuy was an important man and warrior of the Eora nation. In December 1790 he gained notoriety after spearing, and killing, Governor Phillip’s gamekeeper. He then went on to lead raids on many of the settlements in the Sydney area, including Parramatta. David Collins, the lieutenant-governor, acknowledged that he was ‘a most active enemy’; however, he also noted that Pemuluwuy’s attacks were precipitated by the vicious ‘misconduct’ of the colonisers. In 1801 Governor King issued a proclamation that Indigenous people could be shot on sight, and placed a bounty on Pemuluwuy. He was murdered by a settler in 1802 and his body was subsequently desecrated. (Exhibition text)

![John Heaviside Clark (draughtsman Scotland 1770-1863, England 1801-32) Matthew Dubourg (engraver active in England 1786-1838) 'Climbing trees' 1813 (installation view)]()

John Heaviside Clark (draughtsman Scotland 1770-1863, England 1801-32)

Matthew Dubourg (engraver active in England 1786-1838)

Climbing trees (installation view)

Plate 4 from Field Sports &c. &c. of the Native Inhabitants of New South Wales, published by Edward Orme, London

1813

Hand-coloured aquatint

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gurnett-Smith Bequest, 1999

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Field Sports &c. &c. of the Native Inhabitants of New South Wales was the first publication to focus on the representation of Indigenous Australian life. The set of ten colour aquatints was part of a much larger series called Foreign Field Sports, which depicted sporting and hunting pursuits from around the world. These prints contain accurate details, such as the spearthrower, however, the plants and animals are inaccurate and were clearly unfamiliar to the London artists who made them, neither of whom came to Australia. (Exhibition text)

![John Heaviside Clark (draughtsman Scotland 1770-1863, England 1801-32) Matthew Dubourg (engraver active in England 1786-1838) 'Warriors of New S. Wales' 1813 (installation view)]()

John Heaviside Clark (draughtsman Scotland 1770-1863, England 1801-32)

Matthew Dubourg (engraver active in England 1786-1838)

Warriors of New S. Wales (installation view)

Plate 6 from Field Sports &c. &c. of the Native Inhabitants of New South Wales, published by Edward Orme, London

1813

Hand-coloured aquatint

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gurnett-Smith Bequest, 1999

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

The Flinders and Baudin expeditions

Between 1801 and 1804, skilled British navigator Matthew Flinders and his crew aboard the Investigator circumnavigated Australia, funded by the Royal Society and its president Sir Joseph Banks. Their directive was to chart the final stretch of southern coastline that remained unknown on European maps, and learn more about the continent’s extraordinary natural history. A similar French expedition led by Nicolas Baudin on the Géographe and the Naturaliste had already commenced (1800-04). Sent by the Marine Ministry and Napoleon Bonaparte, the expedition sought to map and explore the unfamiliar land and its inhabitants; however, the British feared that it was a reconnaissance mission with a view to founding a French base in New Holland or Van Diemen’s Land.

The most dazzling record of both voyages’ scientific achievement was produced by the artists on board. Travelling with Baudin on the Géographe was Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, who delineated thousands of animal specimens, and Nicolas-Martin Petit, who represented the Aboriginal people encountered on the voyage. Their drawings were the basis for the engravings published in the official account of the expedition, Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands (1807–11). Aboard the Investigator was the mature natural history artist Ferdinand Bauer and the talented young landscape painter William Westall. (Text from the NGV website)

![New Holland: New South Wales. View of the southern part of the town of Sydney]()

Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (draughtsman, France 1778-1846)

Victor Pillement (engraver, France 1767-1814)

Marie-Alexandre Duparc (engraver, active in France 18th century – 19th century)

New Holland: New South Wales. View of the southern part of the town of Sydney (Nouvelle-Hollande: Nouvelle Galles du Sud. Vue de la partie meridionale de la Ville de Sydney)

Plate 38 from Voyage de Découvertes aux Terres Australes (Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands) atlas, by François Peron and Louis de Freycinet, published by L’Imprimerie Impèriale, Paris, 1807-16

Etching and engraving

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through the NGV Foundation by John Baird, Member, 2005

Following their lengthy voyage and exploration of the south-east coastline of Australia, the Géographe and Naturaliste struggled into Port Jackson in June 1802. The French crew remained there for five months to recover and repair their ships. The surveying and scientific parties continued with their work, to some British suspicion, and Charles-Alexandre Lesueur drew scenes of Sydney and its surrounds, as well as exquisite natural history records. Taken from their camp on Bennelong Point (where the Sydney Opera House now stands) this view looks across Sydney Cove to where The Rocks and the southern end of the Harbour Bridge are now. (Exhibition text)

![Ferdinand Bauer (Austria 1760-1826, England 1787-1801, 1805-14, Australia 1801-05) 'Gymea Lily' 1806-13, published 1813 (installation view)]()

Ferdinand Bauer (Austria 1760-1826, England 1787-1801, 1805-14, Australia 1801-05)

Gymea Lily (installation view)

1806-13, published 1813

Plate 13 from Illustrationes florae Novae Hollandiae, sive icones generum quae in Prodromo Novae Hollandiae et insulae van Diemen decripsit Robertus Brown, published London 1813

Colour engraving with hand-colouring

36.2 x 24.3 cm irreg. (image) 39.0 x 25.2 cm (plate) 51.0 x 34.0 cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 2004

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Ferdinand Bauer. 'Banksia coccinea' 1806-13]()

Ferdinand Bauer (Austria 1760-1826, England 1787-1801, 1805-14, Australia 1801-05)

Banksia coccinea

1806-13, published 1813

Plate 3 from Illustrationes florae Novae Hollandiae, sive icones generum quae in Prodromo Novae Hollandiae et insulae van Diemen decripsit Robertus Brown, published London 1813

Colour engraving with hand-colouring

36.2 x 24.3 cm irreg. (image) 39.0 x 25.2 cm (plate) 51.0 x 34.0 cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 2004

Austrian-born Ferdinand Bauer is recognised as one of the most accomplished natural history artists who did much of his art while travelling, both in the Mediterranean and then as an official artist on Matthew Flinders’ circumnavigation of Australia (1801-03). Working closely with botanist Robert Brown, Bauer produced over 2000 drawings and watercolours, and continued with his meticulous work upon his return to London. This engraving exemplifies his skill: it is engraved, printed in colour and then carefully handpainted, all by Bauer himself. Regrettably his intended botanical publication ran to only fifteen plates. (Exhibition text)

![Barthélemy Roger. 'Y-erran-gou-la-ga' 1824]()

Barthélemy Roger (engraver, France 1767-1841)

Nicolas-Martin Petit (after) (draughtsman, France 1777-1804)

Y-erran-gou-la-ga, a native of the environs of Port Jackson (Y-erran-gou-la-ga, suavage des environs du port Jackson)

1824

Plate 24 in the Voyage de Découvertes aux Terres Australes (Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands) atlas

Arthus Bertrand, Paris, 1824, 2nd edition

Hand-coloured engraving, etching and stipple engraving printed in black and brown ink

31.5 x 24.1 cm (plate) 36.5 x 27.6 cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Joe White Bequest, 2010

![William Westall. 'Chasm Island, native cave painting' 1803]()

William Westall (England 1781-1850, Australia 1801-03)

Chasm Island, native cave painting

1803

Watercolour

26.7 x 36.6 cm

National Library of Australia, Canberra

![William Westall. 'A view of King George's Sound' 1802]()

William Westall (England 1781-1850, Australia 1801-03)

A view of King George’s Sound

1802

Watercolour and pen and brown ink

27.9 x 42.9 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1978

William Westall was one of two artists who accompanied Matthew Flinders on the Investigator as it circumnavigated Australia between 1801 and 1803. This highly finished watercolour of King George’s Sound in south-western Australia is not a topographical study, but a romantic vision of a vast, silent and forbidding land. Two generic Aboriginal people figures are included in the foreground in the guise of the noble savage. Their classicised robes and the lack of a European presence, particularly the explorers encountering them, shows Westall casting the scene in an Arcadian period prior to British encounter. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne featuring the Bowman flag 1806 Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Mary Bowman (attributed to) (active in Australia early 19th century)

Bowman flag

1806

Oil on silk

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Presented by John Bowman’s great grandchildren to Richmond Superior Public School, 1905; transferred to the Mitchell Library by the Dept. of Public Instruction, 1916

Made to commemorate Lord Nelson’s naval victory at Trafalgar, this remarkable flag was flown at Scottish free settler John Bowman’s farm in 1806. The first Australian-made flag, it features the earliest recorded image of a kangaroo and emu supporting a shield, one hundred years prior to the implementation of the current coat of arms. According to family members, the Bowman flag was made from the silk of Honor Bowman’s wedding dress and sewn by her daughter Mary Bowman; however, more recent analysis suggests the design was most likely commissioned from a professional sign painter. (Exhibition text)

![John Lewin (England 1770 - Australia 1819, Australia from 1800) 'Koala and young' 1803]()

John Lewin (England 1770 – Australia 1819, Australia from 1800)

Koala and young (installation view)

1803

Watercolour and gouache

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Purchased from a descendant of Governor King, 1983

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Surprisingly, koalas were not captured by colonists until 1803, although their existence had been known of for several years, and they were described as cullawine or colo, the names used by Aboriginal hunters. In August 1803 a female and two joeys were taken to Sydney, where they were reported in the recently founded Sydney Gazette. After one joey died, the mother and surviving joey were painted, proficiently by the Sydney-based artist John Lewin, and exquisitely by expedition artist Ferdinand Bauer. Bauer was unable to complete his watercolour in time to be sent on a departing ship, and thus Lewin’s was the first visual record of this animal to reach England. (Exhibition text)

![John Lewin. 'The gigantic lyllie of New South Wales' 1810]()

John Lewin (England 1770 – Australia 1819, Australia from 1800)

The gigantic lyllie of New South Wales

1810

Watercolour

54.1x 43.6 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Purchased 1968

Natural history

In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the world was being studied and described by Europeans on a scale never seen before. Exploration in the Pacific revealed unanticipated communities and environments and the vast quantities of material brought back – objects, artefacts, specimens, maps, records, descriptions – were regarded with awe and astonishment. Enlightenment ambitions to understand the world through empirical observation led to intense scientific scrutiny, as people sought to comprehend and to classify this exciting, bemusing abundance. In this period, visual imagery became increasingly important, far exceeding a written description and surpassing dried or dead specimens in its ability to depict form, texture, colour, oddity and beauty.

From the time of the British landing in 1770, the people of Britain and Europe were astounded by what they saw in the colony. Captain (later Governor) John Hunter wrote ‘it would require the pencil of an able limner [artist] to give a stranger an idea of [the colourful birds], for it is impossible by words to describe them’. John Lewin was the first professional artist to arrive in New South Wales. Trained in natural history illustration and printmaking, Lewin promptly began drawing and making etchings of local moths and birds perched on Australian plants. (Text from the NGV website)

![Unknown. 'The kanguroo, an animal found on the coast of New Holland' 1773]()

George Stubbs after (England 1724-1806)

Unknown (etcher active in England 1770s)

The kanguroo, an animal found on the coast of New Holland

1773

Plate in An Account of the Voyages undertaken … for making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere by John Hawkesworth, printed for W. Strahan and T. Cadell, London, 1773

Etching

Rare Books Collection, State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Of all the ‘discoveries’ made in Australia by the crew of the Endeavour, one completely unexpected creature captured European imaginations; an animal, Cook wrote, like a greyhound except that ‘it jump’d like a Hare or Deer’. Several of these were caught in northern Queensland where they were called gangurru by the local Guugu Yimithirr. In London, Banks commissioned leading animal painter George Stubbs to paint the kangaroo, although he had only skins, skulls and sketches by Parkinson as his guide. This painting was reproduced in the official account of the voyage, published in 1773, two years after the Endeavour returned home. (Exhibition text)

![Installation views of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation views of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with at second right top in the bottom image, James Sowerby’s Embothrium speciosissimum (now Telopea speciosissima) 1793

Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![James Sowerby. 'Embothrium speciosissimum (now Telopea speciosissima)' 1793]()

James Sowerby (England 1757 – France 1822)

Embothrium speciosissimum (now Telopea speciosissima)

1793

Plate 7 from A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland, part 2, by James Edward Smith, published by James Sowerby, London 1793

Hand-coloured etching and gum arabic

23.6 x 16.0 cm (image and plate), 30.0 x 23.2 cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Joe White Bequest, 2015

A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland by the preeminent English botanist James Edward Smith was the first book dedicated to the study of Australia’s flora. The publication was illustrated by one of England’s leading botanical artists, James Sowerby, who was working from drawings made by John White, surgeon-general of New South Wales, as well as from dried specimens. The detailed illustrations and use of proper Latin names in Smith and Sowerby’s publication follows the authors’ intention to publish a scientific book that also reached a lay audience. (Exhibition text)

![Richard Browne (illustrator) 'Insects' 1813]()

Richard Browne (illustrator, Ireland 1776 – Australia 1824, Australia from 1811)

Insects

1813

Page 52 in Select Specimens from Nature of the Birds Animals &c &c of New South Wales collected and arranged by Thomas Skottowe 1813

Watercolour

18.7 x 30.0 cm (page)

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Bequeathed by D.S. Mitchell, 1907

Convicts with artistic talent were often put to work by their overseers. This was the case for convict Richard Browne who was assigned to Newcastle commandant Thomas Skottowe. Browne hand-painted the illustrations in Skottowe’s 1813 book, Select Specimens from Nature. Upon his release, Browne returned to Sydney, where he continued to paint stylised images of emus, lyrebirds and other animals. He also made portraits of Awabakal and Eora individuals, with the intention of selling these drawings to the developing local market, or as souvenirs to people aboard visiting ships. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation views of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with in the bottom image at right, John Lewin’s Fish catch and Dawes Point, Sydney Harbour c. 1813; and second right, John Lewin’s Platypus 1810

Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

John Lewin

Fish catch and Dawes Point, Sydney Harbour (detail)

c. 1813

Oil on canvas

86.5 x 113.0 cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Gift of the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation and South Australian Brewing Holdings Limited 1989

Given to mark the occasion of the Company’s 1988 Centenary

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![John Lewin. 'Fish catch and Dawes Point, Sydney Harbour' c. 1813]()

John Lewin (England 1770 – Australia 1819, Australia from 1800)

Fish catch and Dawes Point, Sydney Harbour

c. 1813

Oil on canvas

86.5 x 113.0 cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Gift of the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation and South Australian Brewing Holdings Limited 1989

Given to mark the occasion of the Company’s 1988 Centenary

In 1812, John Lewin wrote to a friend that he had two oil paintings underway, one of which is believed to be this unusual composition of a haul of fish caught in Sydney Harbour set against the background of Dawes Point (now The Rocks, Sydney). It is thus the earliest oil painting known to have been produced in Australia. Pictured in the composition are various identifiable fish varieties, including a crimson squirrelfish, estuary perch, rainbow wrasse, sea mullet and hammerhead shark, later named the Zygaena lewini (now Sphyrna lewini) after the artist. (Exhibition text)

![John Lewin (England 1770 - Australia 1819, Australia from 1800) 'Platypus' 1810]()

John Lewin (England 1770 – Australia 1819, Australia from 1800)

Platypus

1810

Watercolour and gouache

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Bequeathed to the Trustees of the National Art Gallery of N.S.W. by Helen Banning; transferred to the Mitchell Library 1913

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Sydney Bird Painter. 'Black Swan' c. 1790]()

Sydney Bird Painter

Black Swan

c. 1790

Watercolour and ink

48.1 x 29.2 cm

Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth

Images of the black swan, as well as living birds and skins, were sent back to a fascinated Europe. One depiction became the pose de rigueur – a swan afloat, shown in profile like a heraldic symbol, with wings raised to show the white flight feathers. Like the Stubbs kangaroo, this black swan appeared in numerous forms. This beautiful watercolour was painted by an unidentified artist, possibly a member of the First Fleet, whose hand has also been identified in a volume of watercolours depicting birds held in the Mitchell Library, Sydney. Two or three artists made these drawings, and they are now collectively referred to as the Sydney Bird Painter. (Exhibition text)

![Peter Brown. 'Blue-bellied parrot' 1776]()

Peter Brown (active in England 1758-99)

Blue-bellied parrot

1776

Plate VII in New Illustrations of Zoology: Containing Fifty Coloured Plates of New, Curious, and Non-Descript Birds, with a Few Quadrupeds, Reptiles and Insects, published by B. White, London 1776

Hand coloured etching

19.0 x 24.6 cm (image and plate), 24.0 x 30.5 cm (sheet)

Special Collections, Deakin University, Melbourne

It is unusual to know about an individual bird but this rainbow lorikeet (as it is now known) was captured at Botany Bay by Tupaia, the skilled Polynesian navigator and arioi (priest) who joined the Endeavour in Tahiti. The bird was taken back alive to London, and presented by Joseph Banks to the wealthy collector Marmaduke Tunstall. A watercolour of it was painted in 1772, and this print was published in 1776, carefully hand-coloured to show the bird’s distinctive plumage. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with at centre, Joseph Lycett’s Inner view of Newcastle c. 1818

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Joseph Lycett. 'Inner view of Newcastle' c. 1818]()

Joseph Lycett (England c. 1775-1828, Australia 1814-22)

Inner view of Newcastle

c. 1818

Oil on canvas

59.6 x 90.0 cm

Newcastle Art Gallery, Newcastle

Purchased with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund, London UK 1961

Forger Joseph Lycett was sent to the secondary penal settlement in Newcastle in 1815 after reoffending. His artistic skills soon attracted the patronage of Commandant Captain James Wallis, and under his direction he produced several paintings and drawings for etchings of birds and the landscape, as well as keenly observed watercolours of the local Awabakal people. This view shows the unmistakable profile of Newcastle’s Nobby’s Island, a site which is, according to the Awabakal people, the home of a giant kangaroo that was banished from its kin. The crashing of his great tail against the ground is said to be the cause of earthquakes and tremors in the area. (Exhibition text)

Newcastle 1804

A penal settlement was established in Newcastle in 1804 as a place of secondary punishment for convicts. The area was rich in natural resources, including timber in the hinterland, large deposits of coal in the cliffs at the entrance to the harbour and shell middens for lime burning. Reoffenders sent to Newcastle experienced gruelling physical labour extracting these materials and desertion occurred frequently.

Yet, from this brutal setting, a rich body of work was born which represents the first local art movement by settlers within the Australian colonies. Over a decade, two commandants overseeing the settlement, Lieutenant Thomas Skottowe (1811-18) and Captain James Wallis (1816-22), both of whom were appointed by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, used convicts with artistic skills on a range of projects and capital works programs. They set artists to work documenting the Newcastle region and the local flora and fauna in drawings, paintings and prints. Others interacted with the local Awabakal people and produced important visual documents recording specific individuals and their way of life. Convicted forger Joseph Lycett was sent to Newcastle in 1815, and was the most significant artist involved in these projects, executing a group of major oil paintings, numerous watercolours, and drawings for subsequent etchings. (Text from the NGV website)

![James Wallis (Ireland c. 1785 - England 1858, Australia 1814-19) 'View of Awabakal Aboriginal people, with beach and river inlet, and distant Aboriginal group in background' c. 1818 (installation view)]()

James Wallis (Ireland c. 1785 – England 1858, Australia 1814-19)

View of Awabakal Aboriginal people, with beach and river inlet, and distant Aboriginal group in background (installation view)

c. 1818

in his Album of original drawings by Captain James Wallis and Joseph Lycett, bound with An Historical Account of the Colony of New South Wales by James Wallis, published by R. Ackerman, London, 1821 (c. 1817–21)

Watercolour and collaged watercolour

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Purchased 2011

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

This image is one of a number of watercolours painted by Captain James Wallis that were bound into his personal copy of this publication. This naive image shows Awabakal people from the Newcastle region, whose figures have been cut out and collaged over the coastal scene behind. This presents a harmonious relationship between the Awabakal, colonisers and the military. Such a suggestion is at odds with earlier events of April 1816 when Wallis, under the direction of Governor Macquarie, led an armed regiment against Dharawal and Gandangara people south of Sydney, in what is now acknowledged as the first officially sanctioned massacre of Indigenous people in Australia. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing the Dixson collector’s chest c. 1818-20

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

!['Dixson collector's chest' c. 1818-20]()

William Temple (cabinetmaker)

Patrick Riley (cabinetmaker)

John Webster (cabinetmaker)

Joseph Lycett (attributed to) (decorator)

James Wallis (after)

William Westall (after)

Dixson collector’s chest

c. 1818-20

Australian Rose Mahogany (Dysoxylum fraserianum), Red Cedar (Toona ciliata), brass, oil, natural history specimens

56.0 x 71.3 x 46.5 cm (closed)

Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Presented by Sir William Dixson, 1937

The Dixson collector’s chest

The Dixson collector’s chest, c. 1818-20, and its close relation, the Macquarie collector’s chest, c. 1818, are rare examples of colonial ‘cabinets of curiosity’ and among the most fascinating and complex objects of the colonial period. The Macquarie collector’s chest was commissioned and likely designed by Captain James Wallis, commandant of Newcastle, to present to Governor Lachlan Macquarie. It is debated whether the Dixson collector’s chest, on display here, was produced as its prototype or subsequently as a second version.

Crafted by expert convict cabinet-makers from local Australian timbers, the cabinet opens to reveal painted panels by convict artist Joseph Lycett. Several show the Newcastle region, while others are painted after views by exploration artist William Westall. The drawers contain shells and originally would have also held other natural history specimens including birds, insects, coral and seaweed, tagged and arranged fastidiously by shape, colour and/or type. It is believed these specimens were collected with the assistance of the local Awabakal people, as Wallis had an amicable relationship with their kinsman Burigon.

Both of these chests were only discovered in the twentieth century; the example owned by Macquarie was found in a Scottish castle in the late 1970s, while the Dixson collector’s chest was acquired by Sir William Dixson, benefactor of the State Library of New South Wales, from a London dealer in 1937. (Text from the NGV website)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation views of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with in foreground, showing Dress uniform worn by Sir Edward Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary of New South Wales 1832-42; and in the background, Augustus Earle’s Captain John Piper c. 1826 and Mary Ann Piper and her children c. 1826

Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

In the three years he spent in the colonies, Augustus Earle established himself as one of its leading artists, specialising in portraiture. He was commissioned to produce several portraits of prominent officials including surveyor George Evans, also on display; the departing governor, Sir Thomas Brisbane; and this pair of canvases depicting Captain John Piper and his family. Dressed in a uniform of his own design, Piper is portrayed as a man at the height of his power. The accompanying portrait of Mary Ann with four of their thirteen children depicts the family at home. Her gentility is emphasised by her fashionable dress, banishing all trace of her origins as the daughter of First Fleet convicts. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing Dress uniform worn by Sir Edward Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary of New South Wales (detail) 1832-42

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Unknown, England / Australia (maker)

Firmin & Sons, London (button maker England est. 1677)

Dress uniform worn by Sir Edward Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary of New South Wales

1832-42

Wool, silver brocade (appliqué), metal (buttons)

Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney Purchased 1966

Worn by Sir Edward Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary of New South Wales between 1837 and 1856, this dress coat and trousers formed part of Thomson’s official livery. Loosely based on the Windsor uniform, introduced by King George III, the outfit’s striking red collar and cuffs with oak leaf and acorn hand embroidery impart splendour. In the nascent colony, uniforms were a way to differentiate status, easing anxieties about social mobility and instilling discipline and obedience. (Exhibition text)

![Augustus Earle (England 1793-1838, Brazil 1820-24, Australia 1825-28) 'Wentworth Falls' c. 1830 (installation view)]()

Augustus Earle (England 1793-1838, Brazil 1820-24, Australia 1825-28)

Wentworth Falls

c. 1830

Oil on canvas

Rex Nan Kivell Collection: National Library of Australia and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

The intrepid artist and adventurer Augustus Earle arrived in Australia in January 1825 at a time when the economic and social hierarchies of the new colony were still in flux. An accidental émigré, rescued from the tiny island of Tristan da Cunha, where he had been marooned, Earle’s enterprising nature and versatile talents saw him build up a rich visual record of the colonial encounter for local and international audiences. These large oils were produced in England, several years after his return from the colony, and are among the first to evoke the scale and grandeur of the Australian wilderness. (Exhibition text)

![Augustus Earle (England 1793-1838, Brazil 1820-24, Australia 1825-28) 'A bivouac of travellers in Australia in a cabbage-tree forest, day break' c. 1838]()

Augustus Earle (England 1793-1838, Brazil 1820-24, Australia 1825-28)

A bivouac of travellers in Australia in a cabbage-tree forest, day break (see installation photograph below at left)

c. 1838

Oil on canvas

118.0 x 82.0 cm

Rex Nan Kivell Collection: National Library of Australia and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation views of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne with at bottom centre, Augustus Earle’s Portrait of Bungaree, a native of New South Wales c. 1826

Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Bungaree, or Boongaree, (1775 – 24 November 1830) was an Aboriginal Australian from the Kuringgai people of the Broken Bay area, who was known as an explorer, entertainer, and Aboriginal community leader. He is significant in that he was the first person to be recorded in print as an Australian.

By the end of his life, he had become a familiar sight in colonial Sydney, dressed in a succession of military and naval uniforms that had been given to him. His distinctive outfits and notoriety within colonial society, as well as his gift for humour and mimicry, especially his impressions of past and present governors, made him a popular subject for portrait painters.

Bungaree first came to prominence in 1798, when he accompanied Matthew Flinders on a coastal survey as an interpreter, guide and negotiator with local indigenous groups. He later accompanied Flinders on his circumnavigation of Australia between 1801 and 1803 in the Investigator. Flinders was the cartographer of the first complete map of Australia, filling in the gaps from previous cartographic expeditions, and was the most prominent advocate for naming the continent “Australia”. Flinders noted that Bungaree was “a worthy and brave fellow” who, on multiple occasions, saved the expedition. Bungaree continued his association with exploratory voyages when he accompanied Phillip Parker King to north-western Australia in 1817 in the Mermaid.

In 1815, Governor Lachlan Macquarie dubbed Bungaree “Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe” and presented him with 15 acres (61,000 m2) of land on George’s Head. He also received a breastplate inscribed “BOONGAREE – Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe – 1815”. Bungaree was also known by the titles “King of Port Jackson” and “King of the Blacks”. Bungaree spent the rest of his life ceremonially welcoming visitors to Australia, educating people about Aboriginal culture (especially boomerang throwing), and soliciting tribute, especially from ships visiting Sydney. In 1828, he and his clan moved to the Governor’s Domain, and were given rations, with Bungaree described as ‘in the last stages of human infirmity’. He died at Garden Island on 24 November 1830 and was buried in Rose Bay. Obituaries of him were carried in the Sydney Gazette and The Australian.

Text from the Wikipedia website

![Augustus Earle. 'Portrait of Bungaree, a native of New South Wales' c. 1826]()

Augustus Earle (England 1793-1838, Brazil 1820-24, Australia 1825-28)

Portrait of Bungaree, a native of New South Wales

c. 1826

Oil on canvas

68.5 x 50.5 cm

Rex Nan Kivell Collection: National Library of Australia and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Sydney 1810s-50s

The 1810s through to the 1850s was an era of expansion for the colonists who had settled in New South Wales and a time of continuing dispossession for Aboriginal people. Transportation ended in 1840, but convict labour continued to be assigned to assist with building roads and clearing land for pastoralists. The settler population grew and continued to occupy land further inland, north and south of Sydney. Emigration commissioners in London, and advocates within the colony, worked to encourage the arrival of free settlers, particularly women.

Throughout this period Sydney was the local centre of political power, and social and cultural sophistication. Artistic patronage was fostered. This is reflected in the proliferation of images in which nature and civilisation are pleasantly unified; the newly tamed wilderness placed against views of newly constructed Georgian buildings, demonstrating the colony’s ability to create order and flourish. Portraits were also in demand, and not only reflected the material success of prominent families but were commissioned by the expanding middle class. A print industry was established and expanded as the demand for locally produced prints increased. Images of colonial subjects, including portraits of Aboriginal people, account for a significant proportion of the art market at this time. (Text from the NGV website)

![Edward Charles Close (Bengal (Bangladesh) 1790 - Australia 1866, Australia from 1817) 'The costume of the Australasians' c. 1817]()

Edward Charles Close (Bengal (Bangladesh) 1790 – Australia 1866, Australia from 1817)

The costume of the Australasians

c. 1817

In his New South Wales Sketchbook: Sea Voyage, Sydney, Illawarra, Newcastle, Morpeth c. 1817-40

Watercolour

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Purchased 2009

![Installation views of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne featuring Elizabeth Macquarie, Governor Lachlan Macquarie and Lachlan Macquarie junior

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Unknown artist

Elizabeth Macquarie

c. 1819

Watercolour on ivory

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Presented by F. W. Lawson, 1928

Unknown artist

Governor Lachlan Macquarie

c. 1819

Watercolour on ivory

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Presented by Miss M. Bather Moore and Mr T. C. Bather Moore, 1965

Unknown artist

Lachlan Macquarie junior

c. 1817-18

Watercolour on ivory State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Presented by Miss M. Bather Moore and Mr T. C. Bather Moore, 1965

Portrait miniatures were produced in England from the sixteenth century, with the first example on ivory painted in 1707. They remained a popular form of portraiture, as they were both intimate and easy to carry, until photography gradually took over all but the high end of the market. In Australia miniatures were similarly popular with the more affluent colonists. Lachlan Macquarie was the governor of New South Wales from 1810 to 1821. This suite of miniatures, painted in Australia by a skilled but now unknown artist, show Macquarie, his wife Elizabeth and their young son. They were presented to Captain John Cliffe Watts, Macquarie’s aide-de-camp, as a gift and memento of friendship, prior to Cliffe’s return to England in April 1819. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing Henry Gritten’s oil on canvas Hobart, Tasmania 1856 National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1975

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Hobart’s Mount Wellington was a landmark of such majestic beauty that for many it rivalled the magnificent natural harbour of Sydney. The site naturally attracted the pen and brush of many colonial artists including John Glover, Knud Bull and Eugene von Guérard. Henry Gritten, who lived in Hobart from 1856 until at least 1858, painted it many times, and it is almost as common in his oeuvre as his views of Melbourne from the Botanic Gardens of the 1860s. Most artists painted the view from the same vantage point adopted by Gritten, looking across the Derwent River towards the settlement nestled at the foot of the rising mountain. (Exhibition text)

Van Diemen’s Land 1803

In 1803, 160 years after the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman named and charted Van Diemen’s Land, the British laid claim to the island by relocating convicts and officers from New South Wales to forestall any incursion by the French. Convict transports continued to arrive intermittently in Van Diemen’s Land, mostly bringing prisoners from Britain and Ireland, until 1856, by which time more than 72,000 convicts had been sent there. There were several penal settlements established in Van Diemen’s Land, the most notorious of which were at Macquarie Harbour and Port Arthur.

In 1804, a year after the arrival of the first transports of convicts, Hobart Town was founded on the banks of the Derwent River and it quickly became an important southern trading port.

Over the next twenty years the settlement developed into a cultured, albeit provincial, Georgian township. Local sandstone was widely used to build fine buildings, including places of worship and civic and commercial buildings, and in turn the cultural life of the colony developed. In 1822 fifty-eight per cent of the population of Van Diemen’s Land were convicts, and consequently the majority of artists and artisans came from their ranks. (Text from the NGV website)

![Unknown, Tasmania. 'Waistcoat' mid 19th century (installation view)]()

Unknown, Tasmania

Waistcoat (installation view)

Mid 19th century

Wool, cotton, bone

Collection of Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, Hobart

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing Unknown, Tasmania 'Jacket' mid 19th century]()

Unknown, Tasmania

Jacket (installation view)

Mid 19th century

Wool, linen, cotton, bone

Collection of Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, Hobart

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing Unknown, Tasmania Jacket and Indoor cap mid 19th century, wool, linen, cotton, bone

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Unknown

Tasmania Jacket

Mid 19th century

Wool, linen, cotton, bone

Collection of Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, Hobart

Unknown, Tasmania

Indoor cap

Mid 19th century

Wool

Collection of Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, Hobart

All convicts transported to Australia were issued with a set of clothing designed to differentiate between them and to facilitate identification should they attempt to escape. Although most convicts wore what became known as ‘slops’ in plain greys, dark browns and blues – like this jacket – the lowest class of convicts, particularly those with life sentences, were made to wear yellow. Colloquial terms soon emerged to describe these uniforms: a partly coloured black and buff uniform that demarcated reoffenders became known as a ‘magpie’, while the yellow-suited convicts were called ‘canaries’. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing Lion’s head, Book-shaped puzzle box, Bell and Fork mid 19th century

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Unknown, Tasmania

Lion’s head

Mid 19th century

Iron

Collection of Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, Port Arthur

Unknown, Tasmania

Book-shaped puzzle box

Mid 19th century wood

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston Beattie Collection

Unknown, Tasmania

Bell

Mid 19th century

Wood, brass, iron, bronze

Collection of Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, Hobart

Unknown, Tasmania

Fork

Mid 19th century

Wood

Collection of Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, Port Arthur

NGV Australia will host two complementary exhibitions that explore Australia’s complex colonial history and the art that emerged during and in response to this period. Presented concurrently, these two ambitious and large-scale exhibitions, Colony: Australia 1770-1861 and Colony: Frontier Wars, offer differing perspectives on the colonisation of Australia.

Featuring an unprecedented assemblage of loans from major public institutions around Australia, Colony: Australia 1770-1861 is the most comprehensive survey of Australian colonial art to date. The exhibition explores the rich diversity of art, craft and design produced between 1770, the arrival of Lieutenant James Cook and the Endeavour, and 1861, the year the NGV was established.

The counterpoint to Colony: Australia 1770-1861, Colony: Frontier Wars presents a powerful response to colonisation through a range of historical and contemporary works by Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists dating from pre-contact times to present day. From nineteenth-century drawings by esteemed Wurundjeri artist and leader, William Barak, to the iridescent LED light boxes of Jonathan Jones, this exhibition reveals how Aboriginal people have responded to the arrival of Europeans with art that is diverse, powerful and compelling.

Tony Ellwood, Director, NGV said: ‘Cook’s landing marks the beginning of a history that still has repercussions today. This two-part exhibition presents different perspectives of a shared history with unprecedented depth and scope, featuring a breadth of works never-before-seen in Victoria. In order to realise this ambitious project, we have drawn upon the expertise and scholarship of many individuals from both within and outside the NGV. We are extremely grateful to the Aboriginal Elders and advisory groups who have offered their guidance, expertise and support,’ said Ellwood.

Joy Murphy-Wandin, Senior Wurundjeri Elder, said: ‘I am overwhelmed at the magnitude and integrity of this display: such work and vision is a credit to the curatorial team. The NGV is to be congratulated for providing a visual truth that will enable the public to see, and hopefully understand, First Peoples’ heartache, pain and anger. Colony: Australia 1770-1861 / Frontier Wars is a must see for all if we are to realise and action true reconciliation.’

Charting key moments of history, life and culture in the colonies, Colony: Australia 1770-1861 includes over 600 diverse and significant works, including examples of historical Aboriginal cultural objects, early watercolours, illustrated books, drawings, prints, paintings, sculpture and photographs, to a selection of furniture, fashion, textiles, decorative arts, and even taxidermy specimens.

Highlights from the exhibition include a wondrous ‘cabinet of curiosities’ showcasing the earliest European images of Australian flowers and animals, including the first Western image of a kangaroo and illustrations by the talented young water colourist Sarah Stone. Examples of early colonial cabinetmaking also feature, including the convict made and decorated Dixson chest containing shells and natural history specimens, as well as a rarely seen panorama of Melbourne in 1841 will also be on display.

Following the development of Western art and culture, the exhibition includes early drawings and paintings by convict artists such as convicted forgers Thomas Watling and Joseph Lycett; the first oil painting produced in the colonies by professional artist John Lewin; work by the earliest professional female artists, Mary Morton Allport, Martha Berkeley and Theresa Walker; landscapes by John Glover and Eugene von Guérard; photographs by the first professional photographer in Australia, George Goodman, and a set of Douglas Kilburn’s silver-plated daguerreotypes, which are the earliest extant photographs of Indigenous peoples.

Colony: Frontier Wars attests to the resilience of culture and Community, and addresses difficult aspects of Australia’s shared history, including dispossession and the stolen generation, through the works of Julie Gough, Brook Andrew, Maree Clarke, Ricky Maynard, Marlene Gilson, Julie Dowling, S. T. Gill, J. W. Lindt, Gordon Bennett, Arthur Boyd, Tommy McRae, Christian Thompson, and many more.

Giving presence to the countless makers whose identities have been lost as a consequence of colonialism, Colony: Frontier Wars also includes a collection of anonymous photographic portraits and historical cultural objects, including shields, clubs, spear throwers and spears, by makers whose names, language groups and Countries were not recorded at the time of collection. Challenging global museum conventions, the exhibition will credit the subjects and makers of these cultural objects as ‘once known’ rather than ‘unknown’.

Press release from the National Gallery of Victoria

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing William Francis Emery’s (active in Australia c. 1850-65) oil on canvas View of Ipswich from Limestone Hill c. 1861 Ipswich Art Gallery Collection, Ipswich

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne featuring 19th century earthenware and stoneware

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Left

Andreas Fritsch (Germany 1808 – Australia 1896, Australia from 1849)

Teapot

c. 1850

Earthenware

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of W. G. Tuck, 1972

Middle

Andreas Fritsch (Germany 1808 – Australia 1896, Australia from 1849)

Coffee pot

c. 1850

Earthenware

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of W. G. Tuck, 1972

Right

Trewenack, Magill, South Australia (pottery 1853-1928)

John Henry Trewenack (potter England 1853 – Australia 1883, Australia from 1849)

Lidded storage jar

c. 1855

Stoneware

National Museum of Australian Pottery, Holbrook, New South Wales

This sharply waisted coffee pot, with its flat lid and nipped-in knob, is of a traditional German type. Fritsch arrived in Melbourne from Schwarzenbek in northern Germany in 1849, accompanied by his wife and four children. He showed eight earthenware objects (which may have included this coffee pot and teapot) at the Victoria Industrial Society exhibition in Melbourne in 1851. The Argus commented on 30 January that Fritsch’s exhibits, which earned him a large silver medal, ‘shewed [sic] how little necessity there is for Victoria being dependent in this article on any other portion of the globe’.

![Edward Robert Mickleburgh (England 1814 - late 19th century, Australia from c. 1841-1870s) 'The barque Terror commencing after Sperm Whales' 1840s (installation view)]()

Edward Robert Mickleburgh (England 1814 – late 19th century, Australia from c. 1841-1870s)

The barque Terror commencing after Sperm Whales (installation view)

1840s

Panbone and pigment

Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney

Purchased, 2004

Photo: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

Installation view of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770 – 1861 at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne showing Panoramic view of King George’s Sound, part of the colony of Swan River 1834

Photos: © Dr Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Lieutenant Robert Dale (draughtsman England 1810-53, Australia 1829-33)

Robert Havell junior (engraver England 1793-1878, United States 1839-78)

Panoramic view of King George’s Sound, part of the colony of Swan River

1834

Engraving, colour aquatint and watercolour on 3 joined sheets

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1958

This lengthy and detailed print shows the distinctive coastline viewed from the rocky summit of Mount Clarence, with the recently established government farm at Strawberry Hill and what later became Albany below. Drawn by surveyor Lieutenant Robert Dale and translated into print by Robert Havell in London, it depicts Nyungar and European figures in friendly contact, surrounded by native vegetation and animals. The spectacular view may have enticed prospective investors or settlers, promoting an idyllic vision with its abundance of fertile land and peaceful relations with the Traditional Owners. (Exhibition text)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Colony: Australia 1770 - 1861' at NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne]()